[ad_1]

Born in Missoula, Montana, Lynch was the epitome of an American original. His childhood was steeped in idyllic small-town life that belied the disquieting undercurrents that would later define his work. Moving east to study painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the 1960s, Lynch encountered a cityscape of decay and desolation in Philadelphia. These grim environs became the crucible for his unforgettable debut feature, Eraserhead (1977) — a delirious portrait of industrial alienation that redefined what an independent film could look like. That it found its audience in midnight screenings, among the insomniacs and the curious, is almost poetic.

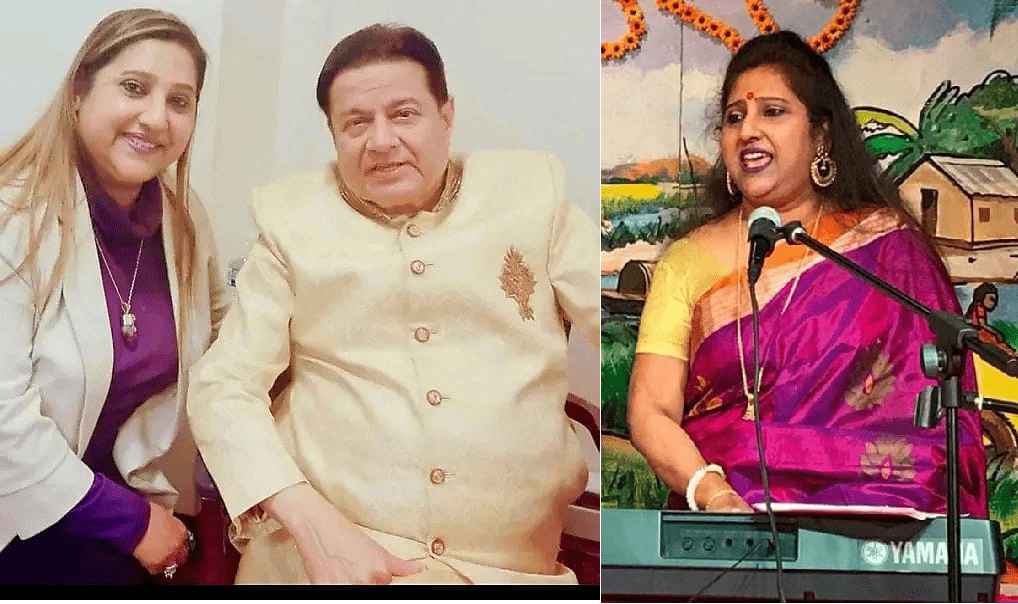

David Lynch

| Photo Credit:

X/ @Criterion

From there, Lynch’s ascent was a paradox of mainstream success and avant-garde sensibilities. The Elephant Man (1980) garnered eight Oscar nominations, earning Lynch his first Best Director nod. Yet, just as Hollywood seemed to embrace him, Lynch delivered his notorious adaptation of Frank Herbert’s sprawling sci-fi epic, Dune (1984), whose troubled production and commercial failure threatened to derail his career. Yet Lynch’s genius seemed to thrive on this selfsame risk and reinvention. With Blue Velvet (1986), he dove headfirst into the sinister underbelly of small-town America, crafting an alluring, disturbing masterpiece of American cinema. It became his signature, the quintessential “Lynchian” work, brimming with suburban rot, voyeurism, and stirring ambiguity.

Perhaps no project epitomises Lynch’s cultural impact more than Twin Peaks. Debuting in 1990, the television series captivated American TV watchers with the enigma of its surreal storytelling. The influence of the ethereal soap opera was unprecedented, laying the groundwork for everything from The X-Files to Stranger Things. Decades later, Lynch returned to this world with Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) — a breathtaking, often confounding 18-hour opus that cemented his status as one of the most visionary filmmakers alive.

Even his failures felt iridescent. The likes of Wild at Heart (1990), which won the Palme d’Or, and Lost Highway (1997) found their audiences over time, becoming staples of cult cinema. Mulholland Drive (2001), initially conceived as a TV pilot, was later crowned the best film of the 21st century (so far) by a BBC poll. His final film, Inland Empire (2006), was an experiment in digital filmmaking, a perplexing narrative that dared those curious enough to lose themselves entirely.

But Lynch was never content with being just a filmmaker. He painted, made music, and proselytized the virtues of transcendental meditation as though inner peace were a paintbrush for the soul. Fans would also fondly remember his daily weather reports on YouTube — perfectly deadpan missives about sunshine and rain clouds, delivered as if the forecast were a metaphor for something you’d never quite grasp.

Lynch’s art, whether in moving images or abstract forms, was never about easy answers. He invited us all into his dreams, often leaving us to parse their meaning or simply sit with the unease they inspired. He was an anomaly, a singular voice who made the macabre and the mundane collide with an explosiveness that was beautiful. Which is probably why his passing feels like the closing of a chapter in art itself.

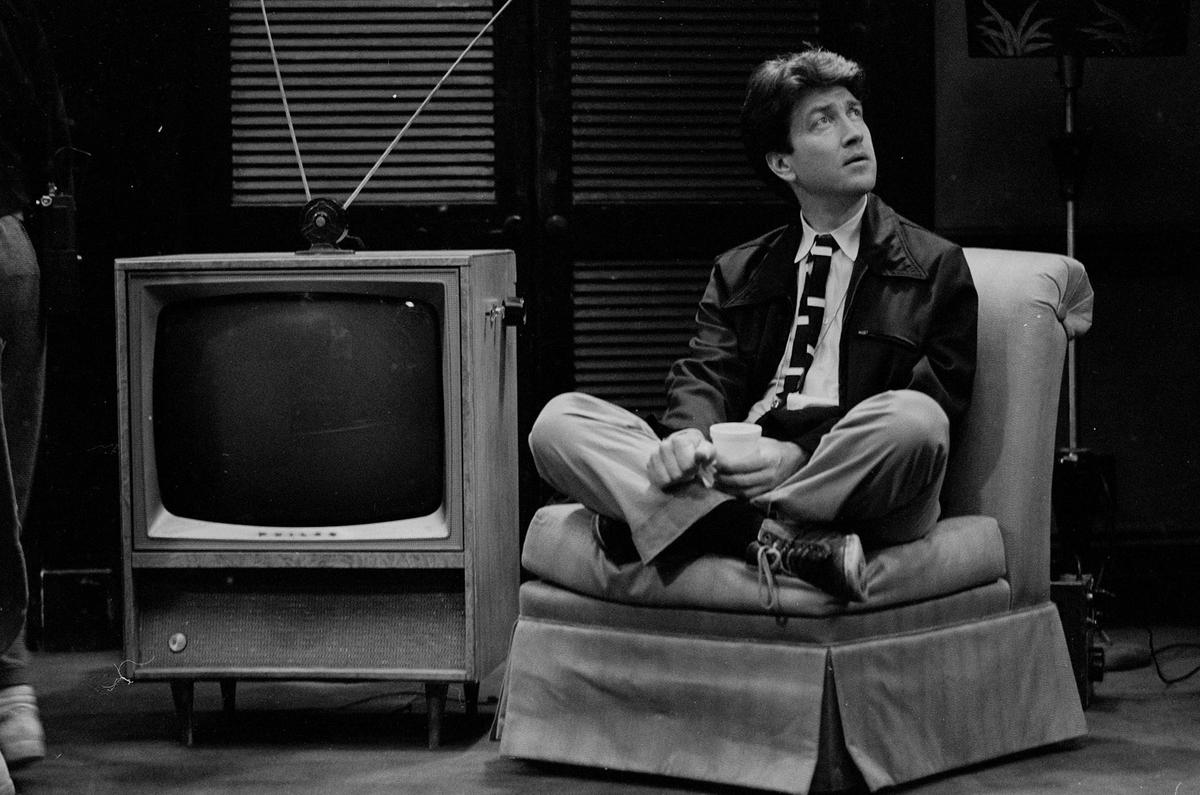

That Lynch’s last on-screen appearance was as the grizzled, irascible gatekeeper of American cinema, John Ford, in Spielberg’s ode to the artform, The Fabelman’s, is the sort of cameo you’d dismiss as too on-the-nose if it weren’t so perfect. Of course, he insisted on wearing the costume for two weeks straight, painting in it, sitting in it, probably staring into the abyss in it, until it emerged authentically wrinkled and lived-in. And of course, he’d negotiate his participation not with money, but with Cheetos. He delivers a menace of a riddle that cinephiles will be doomed to obsess over for decades: “When the horizon’s at the bottom, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s at the top, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s in the middle, it’s boring as s**t. Now, good luck to you — and get the f**k out of my office.”

David Lynch in a still from ‘The Fabelmans’

It’s hard not to see the moment as a reflection of Lynch himself — someone who spent his entire career avoiding the middle, both figuratively and literally. His horizons were always in the extremities, towards where one wouldn’t normally gravitate (“Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole,” does feel a fitting epitaph).

Lynch’s legacy is in the courage he gave us to dream with abandon and to seek the surreal within the everyday. His work always demanded more of you: more curiosity, more patience, and more willingness to get the hell out of your comfort zone. With his departure, it’s almost as if the horizon itself has shifted and left us in a world that feels just a little more middle, a little more boring as s**t.

Published – January 17, 2025 11:31 am IST

[ad_2]

Source link