Each morning as the first rays of the sunlight filtered through the window of our small apartment, I would look at the image of Kalinga Narthana Krishna hanging above my bed.

His divine form filled the room with a presence both powerful and playful. I often found myself in conversation with him, sharing my fears and joys. At times, his gaze seemed intense, almost overwhelming, but at other times, he appeared as a mischievous child, playing with a serpent.

After being fully awake, I would turn to the beautiful shrine in a corner of the room, where Radha and Krishna resided, their forms bathed in the soft glow of the morning light. My mother would with a glass of milk, singing Mira’s bhajan, ‘Jago bansi wale, jago more pyare’. She offered the milk to Krishna, a ritual of love and devotion, leaving it at his feet. I wondered whether he drank it, and kept checking.

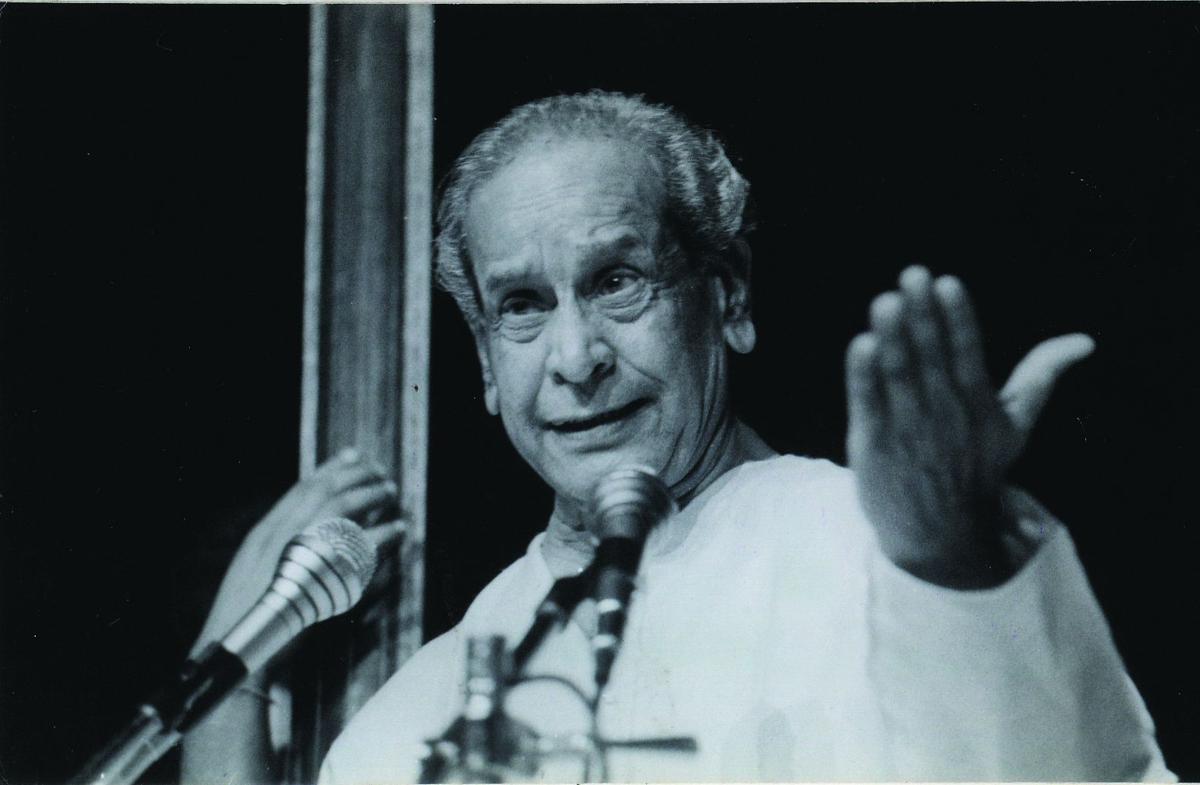

Pt. Bhimsen Joshi’s rendering of ‘Teertha Vithala Kshetra Vithala’ became Aruna Sairam’s favourite abhang.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

My first abhang experience

It was a Sunday. The house buzzed with energy. That evening, Shri Mohan Pai and his abhang mandali would fill our home with the divine sounds of Vithala. We awaited the arrival of fellow devotees, kindred spirits who shared our love for Panduranga. I was particularly excited with the thought of joining the chorus and chanting ‘Vithala, Vithala’ . As dusk fell, the room echoed with Vithala Nama and binding us all in its energy. Years later, Pt. Bhimsen Joshi’s rendering of ‘Teertha Vithala Kshetra Vithala’ became my favourite abhang.

A huge painting of Srinathji occupies a wall of Aruna Sairam’s home in Chennai

| Photo Credit:

R. RAVINDRAN

The midweek melodies

It was a Wednesday, and my mother’s friends arrived for their weekly Meera Bhajan Mandali session. When I returned from school, the house reverberated with their voices. My mother gently beckoned me to join them. I knew she would ask me to sing ‘Maadu meikkum kanne’ at the end, a tradition I cherish to this day.

There is something indescribably beautiful about gazing at Krishna’s form as I sing for him, feeling a connection that transcends the music itself.

Balamma’s divine dance

Balasaraswati mesmerised the audience with her performance of ‘Krishna Nee begane baro’

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

I was in class five, and we were at a dance performance by Bala Saraswati, who was affectionately referred to as Balamma. We eagerly awaited for her rendition of ‘Krishna nee begane baro’. As she stepped onto the stage, her eyes remained fixed at just two feet above the stage. It appeared as if she was looking at little Krishna himself. Throughout the song, her gaze never moved. I was mesmerised by the love, music, and dance that unfolded before me. Balamma’s performance was just dance; it was a conversation with the divine.

Learning from Brindamma

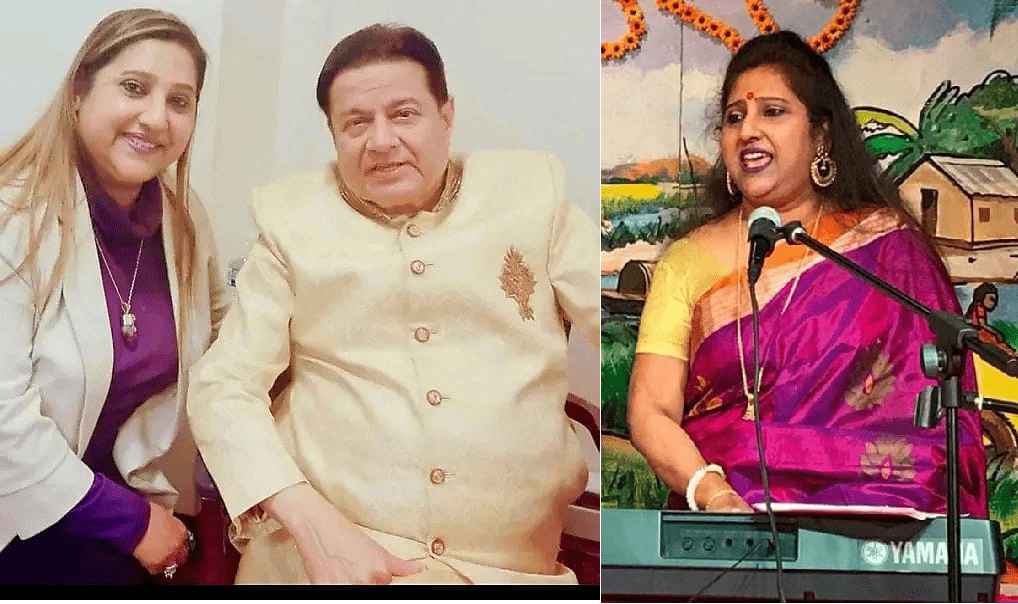

Guru T. Brinda, from whom Aruna learnt Dikshitar’s ‘Chetashree Balakrishnam’, that later became one of her favourite compositions.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Aruna Sairam

As a youngster seated among a small gathering of senior singers, I felt special. Brindamma began teaching a new composition, ‘Chetashree Balakrishnam Bhajare’, and I followed along as best as I could. Some phrases were too intricate for me, but I lingered on the words and the tune, especially the line that began with ‘Nalina Patra Nayanam’. I asked Brindamma what ‘Vata Patra Sayanam’ meant, and she explained that it referred to an endless expanse of blue water, with a small Banyan (aalilai) leaf floating on it, upon which lies little Krishna, all curled up, sucking his toe, a smile on his radiant and alluring face. In Tamil, we call him ‘Aalilai Kannan’. As she described it, I got lost in the lyrics.

The festive Gokulashtami

It was Gokulashtami, and the preparations were underway. Pictures of Krishna’s various leelas were cut and pasted onto a cardboard, and carefully arranged around our little Radha Krishna shrine. There is Vasudeva carrying Krishna in a basket, crossing the Yamuna. I heard someone sing the viruttam ‘Nalliravil pirandu, nadi kadandu, valiya pillai endru emmai aala vanda tavame’, followed by ‘Karuttil niraindai kannil maraindai Kanna’ (composed by Tiruvarur Ramamurthy Bhagavatar).

A chance encounter with the divine

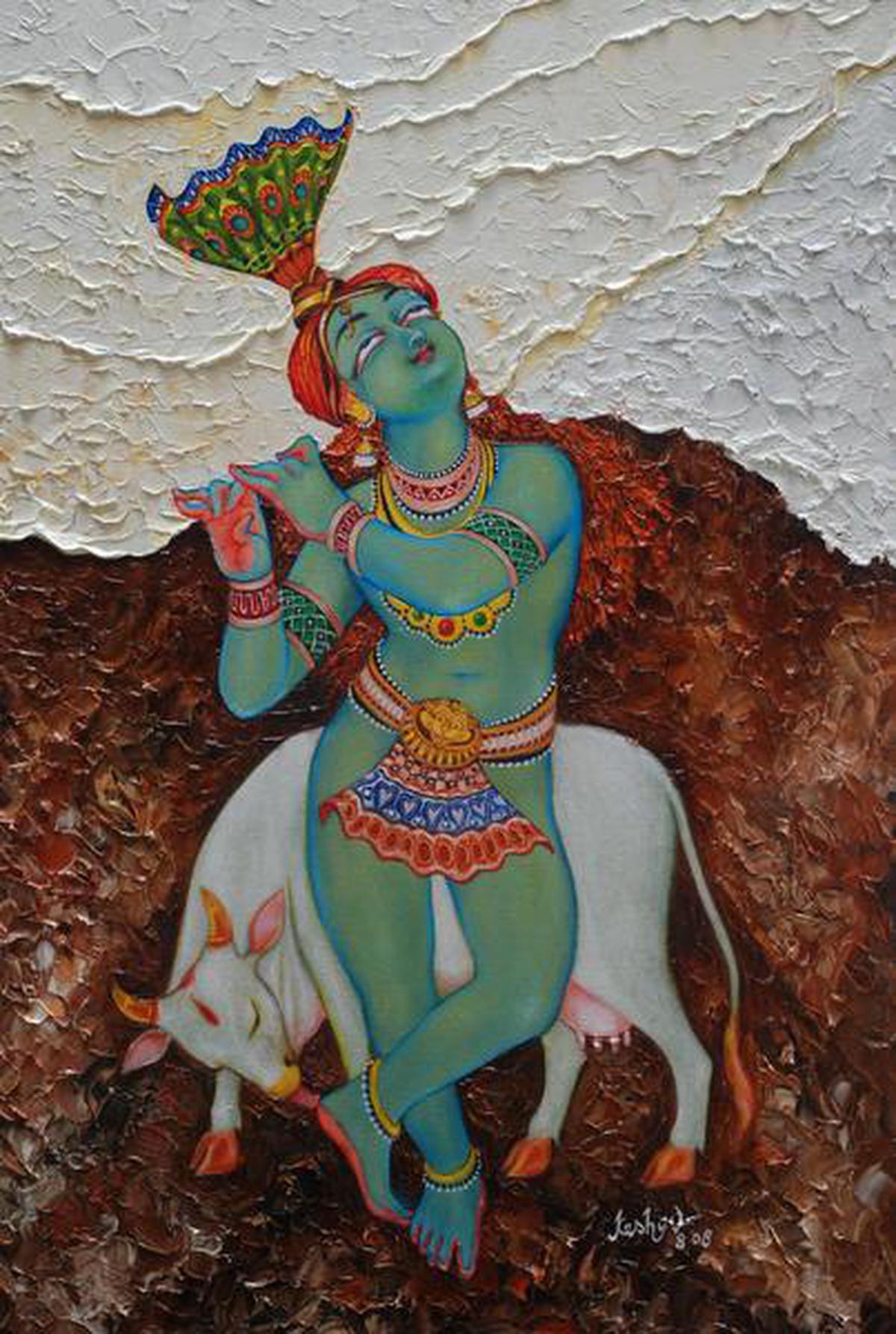

An illustration of Krishna by Keshav.

Many Years later, perhaps in 1994, during a visit to Tiruvarur, my father’s birthplace, we attended the Mummoorthigal Vizha, conducted exceptionally by Lalgudi Jayaraman sir. A fellow rasika, Chandrashekhara Raja accosted us and offered us a precious recording — a cassette of Kalinga Narthana thillana rendered by Needamangalam Krishnamurthy Bhagavatar. He wanted us to copy it immediately and return the original. Back home, when I finally played it, I was moved to tears. This was the song that I had carried in my heart since I was ten. I had heard Needamangalam Bhagavatar sing this thillana through his two-hour upanyasam. He would stop at every line and narrate a story of Krishna.

Later that year, I travelled to Switzerland for a concert tour where I found a cow shed, near the house of friends and hosts Eva and Oti. It was there, with a cassette player in my hand and surrounded by robust Swiss cows, that I relearned the Kalinga Nartana thillana. That weekend, I performed it for the first time, and from that moment, it has belonged to Krishna and to all the bhaktas and rasikas.

Oothukkadu Venkata Subba Iyer must have had a vision of Krishna on Kaliya. To me, this thillana is pure sound born out of a clear vision and emanating from unconditional love for Krishna; a life in Krishna’s melody.