[ad_1]

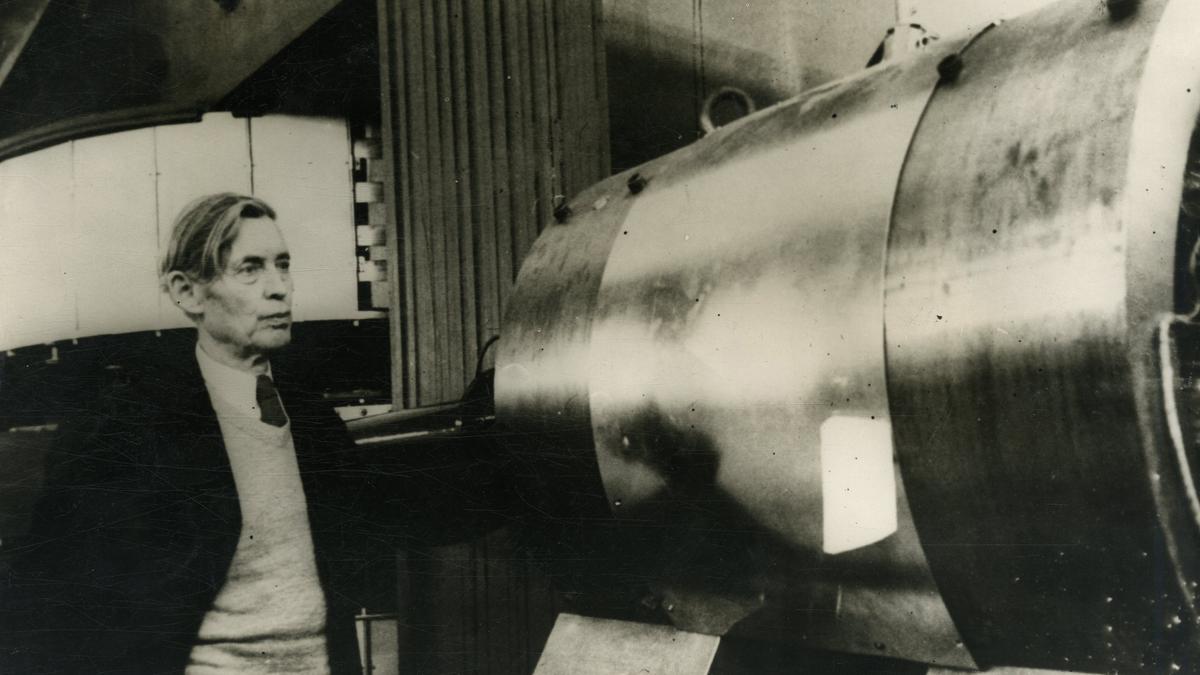

Girish Sahni

| Photo Credit: File photo/The Hindu

On X (formerly Twitter), CSIR said it “mourns the sudden loss” in a 5:40 pm post.

Dr. Sahni joined the Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), a CSIR laboratory in Chandigarh, in 1991. He became its director in 2005, a position he held until he was appointed the CSIR director-general in 2015. He continued to be associated with IMTECH, sources said.

His time at the helm of the CSIR was often tumultuous. In 2016, for example, a product called BGR-34 developed by two CSIR labs in Lucknow came under scrutiny after Prime Minister Narendra Modi praised its allegedly anti-diabetic effects in a speech. It was being sold at the time by a private entity and bore the CSIR logo. Multiple eminent scientists had questioned CSIR’s “moral, ethical, and public health responsibility” over the product’s lack of scientific testing.

But Dr. Sahni’s time as CSIR director-general was more marked by financial issues. In June 2015, the year he assumed charge, the Union government — itself 18 months into the new Bharatiya Janata Party rule — asked CSIR to start paying for half of its expenses in two to three years in a bid to cut spending. Government officials said the move was aimed at guiding CSIR to better serve “national interests”. It also had Dr. Sahni’s full support, who at the time said, “It’s high time Indian scientists rose to the occasion, and not merely published papers to satisfy their natural curiosity.”

Independent scientists flayed the rapid shift to self-financing citing the lack of a funding structure that channelled money from industry for scientific research.

Only two years later, CSIR declared a financial emergency. In 2017, Dr. Sahni had sent a letter to CSIR staffers saying that out of its allocation of ₹4,063 crore in the 2017-2018 Union Budget, “the balance available for laboratory allocations and various new research projects” after capital costs and salaries and pensions was only ₹202 crore — a fraction of the ₹1,200 crore the organisation had said it needed to fund new research projects.

“The crunch was primarily due to the organisation having to meet the increased salary outgo from recommendations of the 7th Pay Commission and a ₹1,650 crore-hit towards meeting pension requirements,” The Hindu had reported.

In the same letter Dr. Sahni had asked for CSIR labs to compile the contents of their “current technology basket (old and new ones) as well as at least one outstanding game-changer technology” that could be licensed to industry, and charged the CSIR Business Development Group with drafting “a strategy paper on the roadmap to market CSIR’s knowledge base” by June 2017. New CSIR projects were also required to include stakeholders to bear the “cost of all temporary manpower, consumables and contingencies” and bear nearly a third of the capital cost.

The money problem disappeared in 2018, however, even though the allocation to CSIR had increased only by 3.3%. Dr. Sahni had expected CSIR labs to raise ₹1,000 crore in revenue per year by 2017, but data released in March 2018 showed the average revenue between 2014 and 2018 was around ₹475 crore per year.

His term as CSIR director-general concluded in August 2018.

As a scientist, Dr. Sahni was known for his research on the formation and alleviation of blood clots and ‘clot buster’ drugs. Among others, he developed clot-specific streptokinase, a drug whose licensing rights were sold to Nostrum Pharmaceuticals in New Jersey, the U.S., in 2006 for $5 million.

[ad_2]

Source link